The pandemic is over

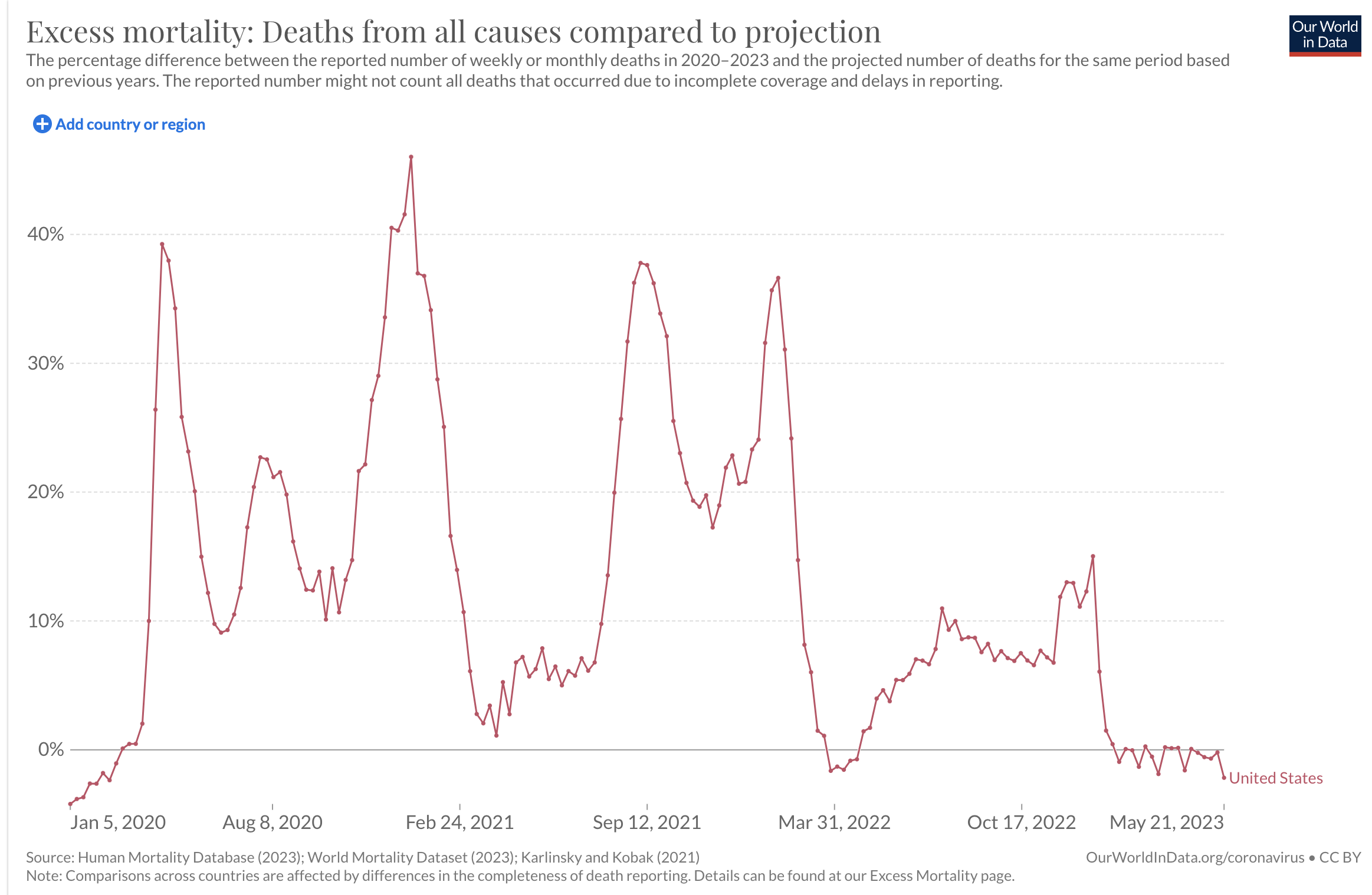

Excess deaths, US, January 2020 to July 2023. Source: Our World in Data.

The COVID-19 pandemic is over

A lifetime ago–April 2020–I wrote the first of four blog posts on the coronavirus “Endgame.” As we floundered through lockdowns and shutdowns and distancing and mask requirements and the race for a vaccine and we felt lonely and afraid and hopeless…we wondered, how will this end?

Now we know. Because as far as I’m concerned, the COVID-19 pandemic is over. The graph above shows why.

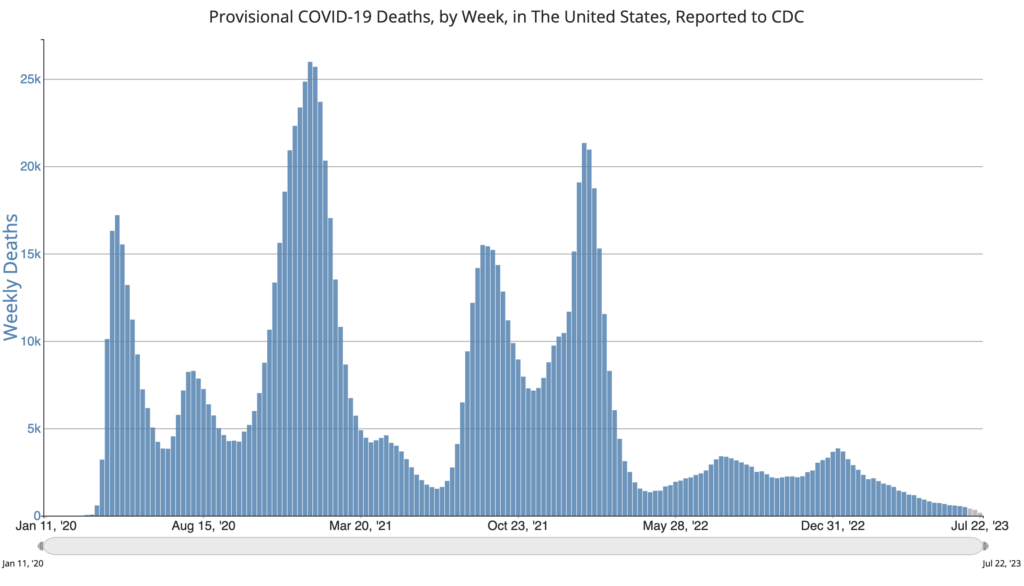

The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is still with us, of course. You can view the CDC’s best guess of COVID-19 deaths per week here. As of July 2023, it’s down to a couple hundred Americans per week. For comparison, at the worst peak in January 2021, the CDC estimates 26,000 Americans died of COVID in one week.

Those numbers have always been controversial. How do you calculate an estimate of COVID deaths when COVID tests were scarce? And what did it mean to die of COVID? If a person died in the hospital of late-stage metastatic cancer but happened to test positive for the virus, did they die of COVID? What if an 85-year-old person had heart failure but was stable, then developed trouble breathing from COVID and spiraled downhill? Did they die of heart failure, or of COVID? And what about people who died of chronic disease like diabetes because the pandemic kept them from proper medical care? Is that a “COVID” death? These questions were widely debated a couple of years ago—usually by people trying to justify an opinion one way or the other on the whole enterprise of flattening the curve.

In August 2020, I entered the fray on this issue by introducing you to the concept of excess deaths. I find this data concept to be very useful in understanding how bad the pandemic was. Excess deaths is a number generated by statisticians. Rather than trying to measure COVID infections or to decide what counts as a COVID-related death, the excess death number simply tells you how many more people died during a particular time period than would be expected from the historical average. The analysis doesn’t care whether they tested positive or had other medical conditions or whether they committed suicide. It told us that the sum of all the things that were happening during the pandemic—both biological and social—was killing people. A lot of people.

As it turns out, the graph of excess deaths over time generally has the same shape as graphs of COVID deaths. Despite the ambiguities and complications I just mentioned, CDC data on COVID deaths represent reality pretty well. The overwhelming majority of excess deaths were caused by viral infections.

Graph: Provisional COVID-19 Deaths, by Week, in the United States, Reported to CDC

Fear and uncertainty

Anyway, two defining features of the pandemic were (1) death and (2) instability. The graphs above illustrate both of these features. In the United States, excess mortality skyrocketed in early 2020. Over the next three years, jagged waves of death followed. Even between viral surges, the number of Americans dying from any cause stayed elevated above the historical baseline.

Until now.

That squiggly tail of data on the right side of the top graph is what “normal” looks like. We are no longer experiencing excess deaths in the US.

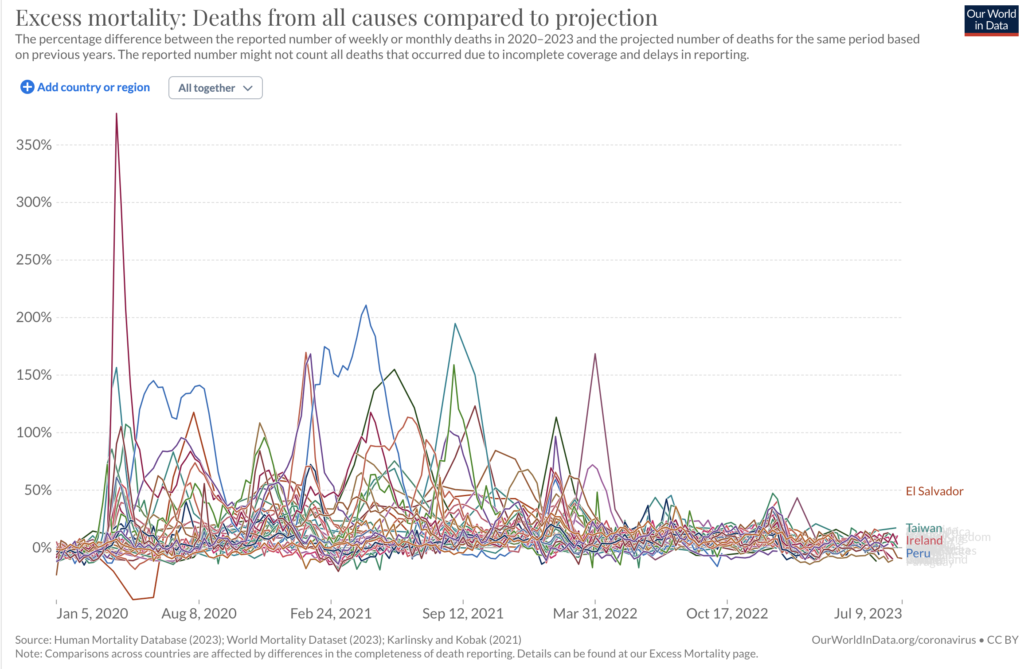

The same is basically true for the rest of the world. (Note the difference in scale on the y-axis: El Salvador, Peru, and some others were hit unbelievably hard.)

Graph: Excess mortality, Most countries

Pandemic uncertainty has also faded away. We used to live in fear of the next wave or the next variant. Would a new form of the virus be more deadly, or more infectious, than the virus that came out of China in early 2020? It’s not entirely clear whether some variants ended up being more lethal than others—it’s hard to measure precisely. But we certainly witnessed the evolution of variants that were more infectious. Omicron swept the globe in late 2021 and now is about the only variant left in the US.

Each variant disturbed whatever uneasy peace we had time and again. It was hard to make plans.

The surges are behind us now. For three years, we have co-evolved with the virus in biological, medical, and social ways. We have reached what I predict will be a stable equilibrium.

As I predicted over three years ago, the pandemic endgame is a combination of herd immunity and effective treatment. “Herd” immunity is what happens when our immune systems work together to the benefit of our community. In an ideal scenario, a person who is immune (due to vaccination or previous natural infection) becomes a dead-end for viral infection and does not transmit the virus to anyone else ever again. The virus would stop circulating for lack of susceptible carriers to spread it, and die out like a forest fire hitting a firebreak.

Unfortunately this pandemic was not “ideal.” COVID-19 is behaving like many other upper respiratory viruses. Immunity does not block reinfection. Plenty of people have had COVID twice or fallen ill after being vaccinated. What immunity does is protect against severe illness and death. COVID is still with us but it has been de-fanged. The excess deaths data prove this point.

Case study: After scrupulous behavior for three years, my in-laws came down with COVID for the first time just a few weeks ago. They are over 80 years old. They’d had four jabs of RNA vaccine and they took Paxlovid within 36 hours of first symptoms. What could easily have been a death sentence in June 2020 was now a common cold (just like the COVID skeptics used to claim.)

I’m not worried about a devastating new COVID variant. I’m worried about the next entirely new virus to jump into humans.

Long COVID

I’ve never really written about Long COVID, so I want to say a few things here. For a significant number of people (according to this study, perhaps 10% of severe COVID cases), medical problems from coronavirus infection linger after the initial respiratory symptoms clear up. The duration can be weeks, months, or even years. Symptoms range from mild to life-altering severity. The list of possible symptoms is as broad as the body itself, but the ones most commonly associated with Long COVID are altered cognition (brain fog and more) and chronic fatigue.

As you can surmise, this vague collection of parameters makes for a poor definition of the syndrome and huge challenges for scientific study. Sadly at this time, there is little I can say that would be definitive. Questions abound regarding prevention and treatment. People in health care may shun Long COVID for its protean nature and their inability to quantify and “fix” it. People in the community may judge the sufferers as morally weak. But it’s clear the disease is real.

Long COVID is not the first example of a post-viral syndrome. The 1918 “Spanish” flu, like our recent coronavirus pandemic, infected a vast number of people. With that huge number of cases, a post-viral syndrome with similarity to Long COVID was revealed in a small percentage. Other viral and bacterial infections are known to trigger lingering illness, especially affecting the brain and nervous system. The mechanism for long-term post-viral syndromes is unknown. There are many possibilities (immune dysregulation; disruption of the microbiome; autoimmunity; persistent virus; blood clotting; brain signaling). If you are interested in Long COVID, I encourage you to follow the science writer Ed Yong. Recently a prominent infectious disease expert, Michael Osterholm of Minnesota, came down with Long COVID. Here is some of his story.

Loss of smell

Early in 2020 when COVID tests were scarce, a telltale sign of infection was losing your sense of smell. I’ve heard little about that lately. It appears that sensory disruption became less common as the virus evolved. Loss of smell or taste is less frequent with the omicron variant (but it still happens). Do victims recover their senses? Most do. One small study showed 96% of COVID patients who lost their sense of smell recovered it within a year. But not all—making anosmia another symptom under the umbrella of Long COVID.

If I Knew Then What I Know Now…

My stomach is churning as I remember in 2020 how angry people were, and afraid. I remember their inability to accept uncertainty. I remember people rejecting science because “science” didn’t have all the answers and the answers kept changing. And I remember other people expecting “science” to make all the hard values-based decisions for them.

There was so much we didn’t know. Is handwashing critical? (Not really.) Does the virus spread through the air? (Yes.) Can you feel fine and unknowingly infect other people? (Yes.) Are healthy children at risk of dying? (Extremely low.) Can you catch it twice? (Yes.) Are the new RNA vaccines safe and effective? (Yes!)

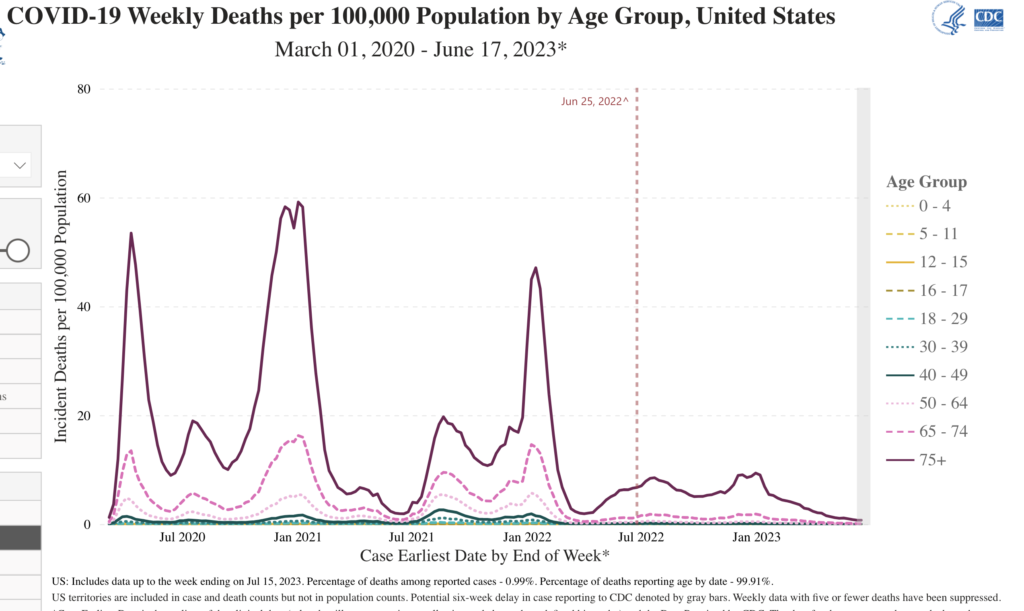

Some of the pandemic uncertainty revolved around the question of who was most at risk of dying from COVID. Now that 1.1 million Americans have died of COVID, we have plenty of data on that. (Remember when COVID deniers said we’d never get to 10,000? When a British academic report in March 2020 predicted 2 million deaths if we failed to take some kind of action, and many pooh-poohed this as hysteria?)

Here are three retrospective graphs on COVID death with answers we sure could’ve used three years ago.

Graph: The Elderly: COVID-19 Weekly Deaths by Age Group

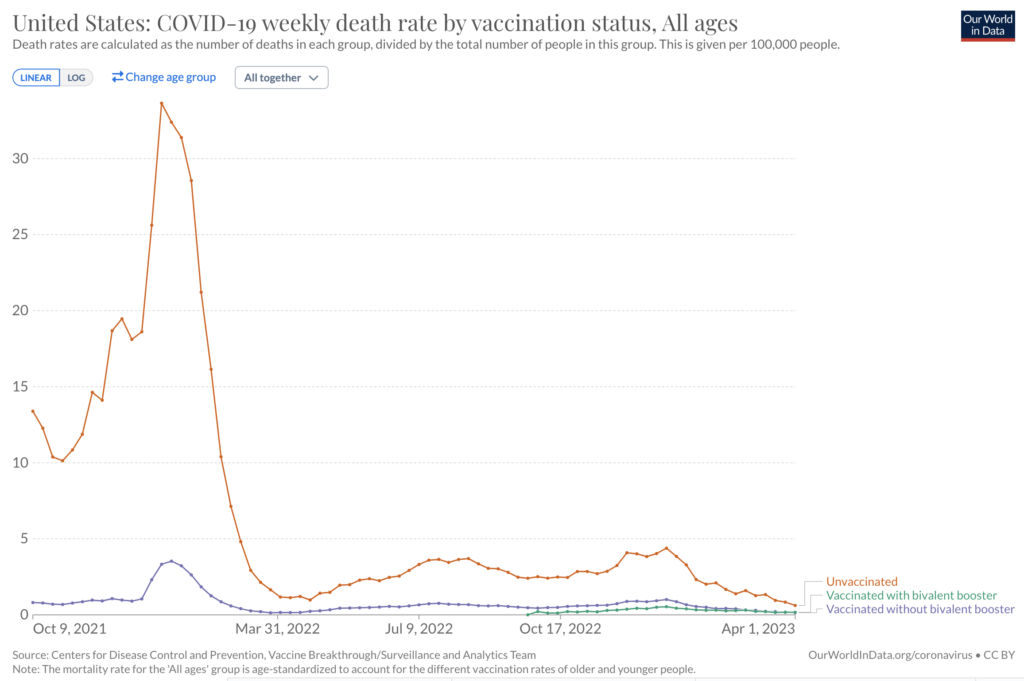

Graph: The Unvaccinated: COVID-19 Weekly Deaths by Vaccination Status

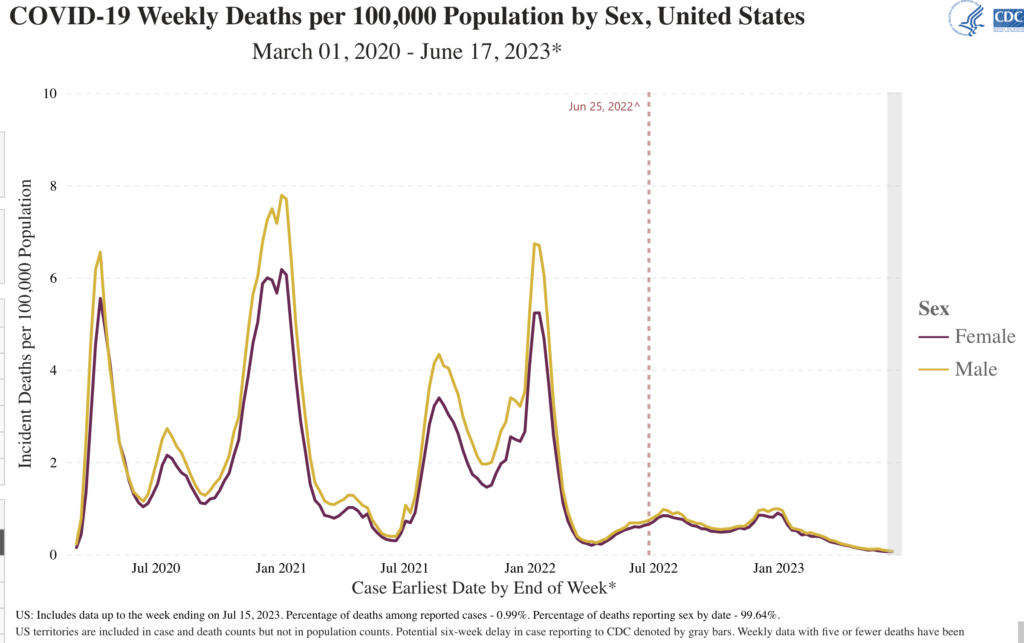

Graph: And what fewer people realize, Men: COVID-19 Weekly Deaths by Sex

Surprises and Progress

In my opinion, the American-made RNA vaccines against COVID-19 are one of the most under-celebrated of all human achievements. Everything about our battle against the virus depended on the hope of a vaccine. Without an eventual vaccine, “flattening the curve” could only space out the fatalities over time. Only a vaccine (or treatment) could reduce the ultimate number of COVID deaths.

The COVID-19 pandemic started at just the right moment in history. More than a hundred years of investment in basic science research in microbiology, molecular biology, and biochemistry had brought us to the brink of being able to invent and mass-produce an effective vaccine against a new virus in a short period of time. COVID pushed us over the brink.

On November 9, 2020, I wrote a blog post about the astonishing data coming from Pfizer’s vaccine trial. Then on December 15, Hubby became one of the first people to receive the shot. Only nine months after the coronavirus upended our lives in the US, we had a vaccine. It felt like a Promethean moment, when a new technology would change everything.

RNA vaccines changed the course of this pandemic and they will forever change humankind’s relationship with future plagues. Their potential application to other areas of medicine, such as cancer treatment, has also been hastened forward by the experience of COVD-19.

Paxlovid

The approval of an oral antiviral medication for COVID-19 is also astonishing. As I explained in another old blog post, it’s really hard to create drugs that treat viral infections (as compared to antibiotics which act against bacteria). Remember remdesivir, an early injectable drug for COVID that had some benefit? Ivermectin, an antiparasitic veterinary drug that skeptics claimed could solve everything? Neither had much of an impact. In December 2021, a full year after the RNA vaccines came out, the FDA gave emergency use authorization to Paxlovid. Paxlovid is an effective antiviral drug, with limitations. It must be given within the first few days of infection. It will not “cure” someone who is already very sick. It does, however, greatly reduce the likelihood of developing severe illness. For many people (like my relatives as I mentioned above), a combination of immunity through vaccination plus an early course of Paxlovid makes COVID infection a minor inconvenience.

Wastewater monitoring

Remember the toilet paper shortages?

That wasn’t the only news story from the bathroom in early 2020. I wrote a post about the use of wastewater monitoring as a public health tool. For quite a while, we didn’t have enough COVID tests to go around. Testing wastewater for the virus became a way to assess what was happening in the community without testing the people. Research on this technology was greatly accelerated by the pandemic. In late 2020, the CDC launched a National Wastewater Surveillance System. While this system was developed to survey for the coronavirus, the system’s infrastructure can be an important public health tool for any future outbreaks. For example, it has been used to keep track of the monkeypox outbreak in the US (data here).

Booster Shots

Basically everyone should already have or should get the “bivalent” COVID vaccine that was approved for adults in late 2022. This vaccine is different from the original vaccines. It contains added protection against some of the Omicron variants.

Future boosters: I recommend that you pay attention to recommendations that will likely come from the CDC, and discuss with your doctor. It’s possible that annual COVID boosters will become the norm, along with the annual flu vaccine. It’s also possible that the cost / benefit analysis will recommend boosters only for older people, or some other conditional recommendation. I’m waiting to see the data.

Wrapping It Up

The writer in me could put down thousands more words about the sequelae of the pandemic. I’ve addressed a couple of medical/public health areas here, ignoring personal, economic, social, political, demographic, and other areas of consequence. The whole experience is just so big. Already for me it begins to feel weirdly remote, like a dream from another lifetime. Looking back at what I wrote reminds me, but I cannot recapture the desolation of 2020. For that, I thank God.

I thank you, my readers, for trusting me in those difficult times. Many of you found ways to express to me how important my work was to you. I started blogging about the pandemic for myself. I continued for all of you. It was a great honor to use my unique gifts as a writer and microbiologist to accompany you on that epic journey.

For the first time, I’m opening this post to comments. Feel free to chime in.

Questions? amy@amyrogers.com

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels at AmyRogers.com.

Amy, I’ve really appreciated the long-form information and commentary you provided through the pandemic. Even when the news wasn’t great, I felt better armed with evidence and a good idea of potential scenarios ahead. Thanks for the expert analysis and clear writing.

Thanks Amy. I have enjoyed reading every one of your blogs over the past few years. Your thoughtful presentation has felt like an unbiased breath of fresh air through uncertain times. I appreciate you.

Dear Amy,

A brilliant analysis of the entire Covid experience. For the past three years, you should have been one of the expert panelists we saw on television day after day. One question which has nagged me for over three years: Why has the US registered such a disproportionate number of Covid cases and deaths, throughout the Covid years? We are 4% of the world’s population, yet the Johns Hopkins numbers continued to allocate 15% or more of the world’s total cases to the US.