The Coronavirus Endgame 2: Social distancing won’t save us

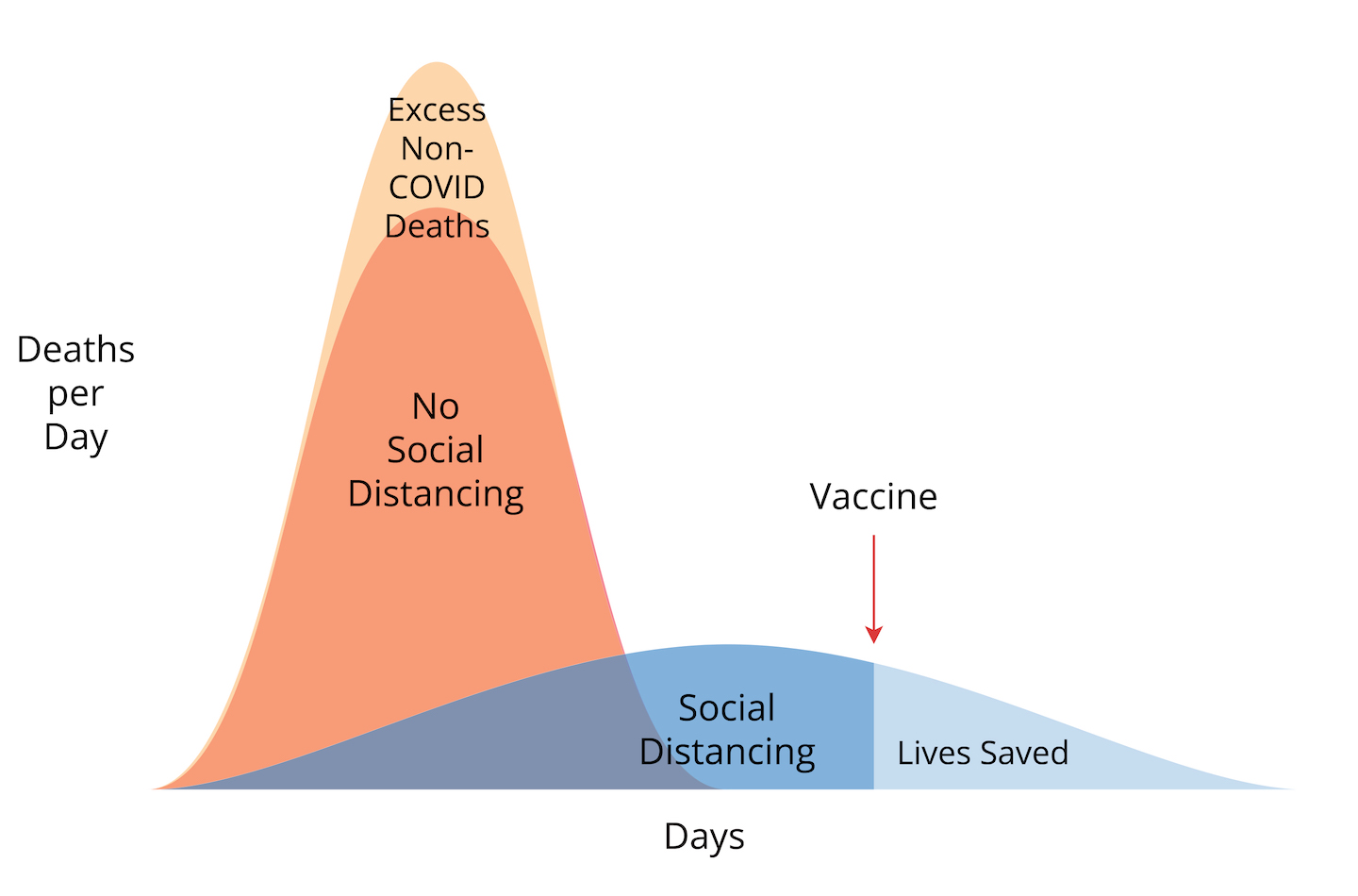

Image courtesy of JRo; curves not to scale

Part 2 of a series on how the pandemic ends, and how we get there. Please share. Link to part 1.

Why Social Distancing Won’t Save Us

Six weeks ago, I wrote a blog post asking the question, is social distancing an overreaction? I said at the time that we had to make decisions based on inadequate information. We still don’t have all the answers we need, but we have a lot of information we did not have in mid-March.

One of my core values, and a value that I find sadly undervalued in our modern political culture, is a willingness to change my position to accommodate new or better information. As the vise of isolation squeezes us, it’s time to think carefully about the trade-offs we’re making, and re-evaluate our strategy for managing the pandemic in light of the latest data.

First, let’s clear up the noise about our goal, strategy, and tactics for battling the pandemic.

“Flattening the curve” doesn’t change the area underneath

Despite the increasingly angry, partisan arguments about tactics, we all share a common goal: to minimize the number of people who ultimately die because of the pandemic. To date, the US has implemented two strategies to reach this goal.

Strategy A: Find a vaccine and / or a cure (a “treatment” is a wimpy version of a cure)

Strategy B: Slow transmission of the virus and decrease fatalities right now

All the chaos you’re hearing about—testing failures and ventilator shortages and masks and school closures and FDA emergency use authorizations and hand washing and social distancing and 14-day quarantines and contact tracing—all are tactics to advance these two strategies.

You can’t argue with Strategy A. (Actually I can, but I’ll save that for my next post.) Let’s talk about Strategy B.

Strategy B is being implemented by “social distancing.” The proper term is non-pharmaceutical interventions, or NPI for short. As the name implies, NPI are all the things we can do to slow the progression of an epidemic in the absence of an actual treatment or vaccine. As the saying goes, it’s not rocket science. NPI tactics have been in use since long before Boccaccio’s 14th-century storytellers of The Decameron sheltered in place during the Black Death.

So what is the purpose of NPI / social distancing? Did it work? Should we continue?

A friend of mine pronounced that she felt duped by social distancing. I can understand why, even though I first described social distancing in my blog on March 2. A lot of people misunderstand its true purpose. I think my friend believed if we did a good job with our NPIs, we would exterminate the virus. (Theoretically, if you could perfectly isolate all humans for two weeks, SARS-CoV-2 would go extinct. But that is not possible. If this virus disappears, it will be luck, not because of our effort.) I saw exhortations on social media saying something like, “the sooner you social distance, the sooner we can get back to normal.” Which is actually the opposite of successful social distancing. Social distancing is all about slowing down the natural evolution of the epidemic, not getting it over quickly.

Why the inflated expectations of what NPIs can accomplish? Partly because we all wanted it to be the answer to our problems, partly because people had difficulty interpreting the graph that shows “flattening the curve,” and partly because social distancing may have been oversold to get people on board.

Here’s what many people think:

By staying home, we save people from dying of COVID-19.

Here’s the truth:

While we stay home, we temporarily protect people from COVID-19.

In the long term, just as many people will die of coronavirus whether or not we social distance. Mathematically speaking, the area under the curve is the same. The only difference is the height of the peak—the peak rate of deaths. Social distancing slows the speed at which we travel, but it doesn’t change our final destination to the endgame.

Then why bother? Why did we social distance at all? Two reasons, illustrated in the graph at the top of this post.

Social distancing flattens the death rate curve and saves the lives of people who would die if their hospital is overwhelmed. This is the upper peak, labeled “excess (non-COVID) deaths.” These excess deaths would include a New York man having a heart attack who can’t get a call through to 911; a woman who dies waiting for an organ transplant that her hospital can’t arrange; a stroke victim who delays treatment too long out of fear to go outside. And it includes some COVID patients; they, too, are more likely to survive if they receive good care, if there are enough ventilators. Flattening the curve protects the health care system.

The second reason is to buy time for a vaccine (or cure, which is unlikely.) If you protect vulnerable people from coronavirus today, they might survive until they can be vaccinated. Only a vaccine (or cure) can meaningfully save lives if the virus remains with us. In the graph, these lives saved are shown in the area under the curve after a vaccine is introduced.

The 1918 pandemic study

Let me go a little deeper on widespread misunderstanding of what social distancing can do, and what it cannot. Recently, many media outlets started talking about a 2007 study of the 1918 influenza pandemic in the US. If you follow this stuff closely, you may have heard comparisons between the public health response in St. Louis versus Philadelphia. Like our current pandemic, the 1918 flu struck an immunologically naïve population, and the only tool they had to fight it was NPIs. Philadelphia waited to take action. A week and a half after the first flu case in town, the city hosted a gigantic parade attended by about 1 in 10 residents. St. Louis, on the other hand, canceled gatherings and asked patients to self-isolate starting only two days after the first local case. The impact of early NPI was enormous. In the following months, St. Louis had a drastically lower peak mortality rate, only 1/8 as high as Philadelphia. In the words of The Atlantic, “During the four-month stretch of the pandemic at the end of the year, Philadelphians were roughly twice as likely as St. Louisans to die from it.”

The important lesson from this historical experiment is that when an epidemic is growing exponentially, early action matters a lot. This year, American governors were right to begin shutdowns before it seemed necessary. The different experiences of New York and California to date are partly explained by the difference of mere days in the start of NPIs.

But pay close attention. STL lowered the peak mortality rate. A rate is a velocity—deaths per day or week. It’s not the distance traveled. During the four months after, STL had relatively fewer deaths from flu.

What happened after that?

In every city, once the NPIs were relaxed, a second wave of deaths occurred. In a press release from the National Institutes of Health about this study,

“Despite the fact that these cities had dramatically different outcomes early on, all the cities in the survey ultimately experienced significant epidemics because, in the absence of an effective vaccine, the virus continued to spread or recurred as cities relaxed their restrictions.”

In 1918, St. Louis “won” social distancing. NPIs successfully diminished the impact of the epidemic by reducing the peak mortality rate. They flattened the curve. But restrictions were necessarily relaxed within weeks, and over the full duration of the epidemic—basically another year—St. Louisans were just as likely to die of flu as people in Philadelphia. Why? Because there was no flu vaccine in those days. The only endgame was herd immunity (and in this particular epidemic, the fortunate disappearance of the virus, partly because of herd immunity.)

I have read multiple reports that obfuscate this fact of the long game, or that misunderstand the difference between a lower peak mortality rate and a lower number of deaths. For example, in one report they say, “As a result, St. Louis suffered just one-eighth of the flu fatalities that Philadelphia saw, according to that 2007 research.” This is flat-out wrong, a consequence, I presume, of innumeracy.

I think I’m repeating myself but I believe this is absolutely vital for all Americans to understand. We have made NPIs/social distancing the bedrock of our pandemic strategy, but it is not a strategy for the long-term course of an epidemic. Early intervention was a wise choice, necessary to put the brakes on an exponentially growing outbreak of a virus we knew little about. But it doesn’t save lives unless other things happen.

Summary of social distancing:

- By slowing transmission of the virus, it reduces the peak mortality rate (flattens the curve)

- Flattening the curve reduces the impact on our health care system. COVID-19 patients can get the best care possible, increasing survival. Hospitals continue to provide excellent care to all other patients as well.

- It buys time to build up hospital capacity; to manufacture ventilators and personal protective equipment; for doctors to learn about the disease and best practices for treating patients; and to create a vaccine.

- It delays deaths from virus infection, spreading them out across the future. It does not prevent coronavirus deaths in the long term unless we get a vaccine.

Thank you, state governors and NBA commissioner and university deans and corporate bosses and church leaders and everyone who took the heat for shutting everything down before COVID-19 was obviously everywhere. Because of your leadership and because Americans have done their part, social distancing has mostly worked. The overwhelming majority of American hospitals are operating just fine. We’ve kept the curve flattened below hospital capacity. We have accomplished Strategy B.

But Strategy B is a fortress in siege, not a parachute. In terms of the pandemic endgame, it freezes us in place. It doesn’t gently carry us toward solid ground. So now what?

It’s time for Strategy C.

Coronavirus Endgame PART 3: Nature doesn’t care whether you think herd immunity sounds evil

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

Sign up for my email list

0 Comments

Share this:

0 Comments