Coronavirus testing 2: Antibody tests for immunity

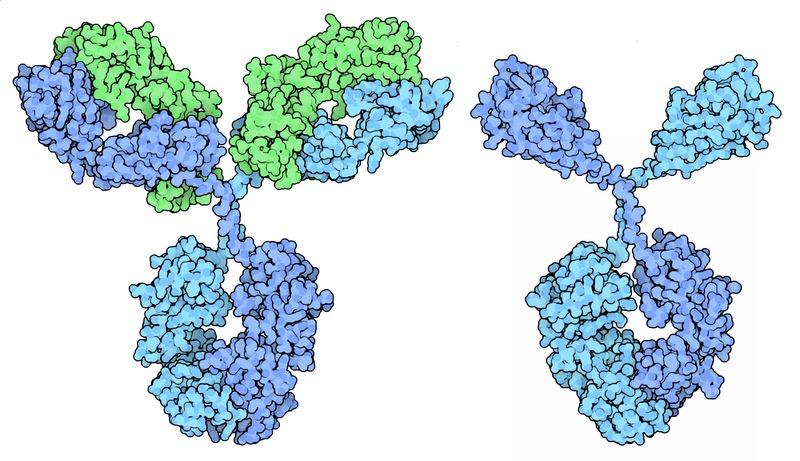

Antibody structure. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Coronavirus tests part 2: Serologic tests for antibodies

As we grapple with the challenge of ending quarantines and resuming group interactions, a powerful tool will be serologic tests for coronavirus antibodies.

In my previous post, I talked about the “coronavirus test,” meaning the diagnostic test that scans for the presence of viral RNA in a swab taken from a person’s nose or throat. Such tests are used to identify people who are actively infected with SARS-CoV-2, whether they have symptoms or not.

An antibody test, or serology / serologic test, does not look for the virus. Instead, it looks at a person’s immune system and asks whether they have done battle against the coronavirus. The evidence is in the immune system’s weapons: antibodies.

Parts of the human immune system learn from experience. In particular, when a new virus infects the body, B lymphocytes (a kind of white blood cell) manufacture antibodies. Antibodies are a class of proteins with one end that sticks, or binds, to a bit of the virus (the antigen). The other end of the antibody activates warrior-cells of the immune system. A staggering number of different antibodies with different antigen-binding ends are made. I’ll skip the details, but over the course of battle, the system figures out which antibodies are most effective at binding the virus. Then it remembers and keeps those particular antibodies around for the next time.

Antibodies exist in your blood, specifically in the liquid component called serum. Serum can therefore be used as medicine. If a person has lots of antibodies against a virus in their serum, you can inject that serum (the antibodies) into a person who is sick. The antibodies will bind to the virus and recruit the sick person’s immune system, possibly helping them to recover.

Antiviral antibodies in a person’s serum tell a history of what viruses the person has encountered at some point. They can even hint at how long ago the infection occurred, because one class of antibodies (IgM) is produced early, and another class (IgG) is produced later.

Convalescent antibody tests, serology tests, coronavirus antibody tests—whatever you want to call them—are being developed and deployed right now in many formats, in many places, to detect antibodies that bind to the new coronavirus. The purpose of these tests is to identify people who have recovered from a SARS-CoV-2 infection, whether they were aware of it or not.

This information is extremely useful for two things.

First, as epidemiologic data. One giant question hanging over this pandemic is, how many asymptomatic or otherwise undiagnosed infections have there been? How prevalent is the virus in the community? Knowing this would help us pin down the mortality rate. The more silent infections there are, the less deadly the virus is. Also, this provides information about herd immunity and how close we are to being able to drop all restrictions.

Second, antibody tests could identify people who are potentially safe to go back to work or into social groups. This would allow us to reactivate ordinary life while minimizing the threat of another disease spike.

But there are some major caveats to this strategy.

- Previous infection does not guarantee protective immunity.

For a variety of reasons, infection by some viruses only happens once in your life. From then on, your immune system is able to fight it off. But other viruses can attack you more than once. Your immune memory isn’t adequate to fully protect you from re-infection. Unfortunately, the “common cold” is an example of a viral infection that you can get again and again. Many “common colds” are caused by coronaviruses. We simply do not know yet whether SARS-CoV-2 is a once-and-done, or an over-and-over kind of infection. A person could have antibodies against the coronavirus but remain susceptible to infection.

- Even if natural infection does lead to protective immunity against SARS-CoV-2, we don’t know exactly what to test for.

Pretend the virus is a box of crayons. Each crayon is a potential antigen (a target for an antibody). Let’s say the virus needs red and blue to make you sick. Neutralizing the yellow, green, orange, and white crayons does not fully disable the virus. Now imagine you have a test that can detect antibodies against all the colors in the virus. You test a person’s blood and find antibodies against red, orange, and white. Clearly this person has encountered the crayon-virus. But is this person protected? In order to interpret the test result, you would have to know which colors confer protective immunity, and which ones are not good enough.

With SARS-CoV-2, we can make educated guesses but we don’t yet know for sure which antigens are important for immunity.

This is also the challenge with creating a vaccine, by the way. Which antigens (colors) should be used?

Another interesting angle is legal liability. If a serology test is used to determine whether an individual person may engage in a riskier behavior (such as, working in a hospital or grocery store), then the manufacturer of the test could conceivably be liable if the person subsequently gets COVID-19. Companies developing such tests need to be given protection from getting sued, because with the current state of knowledge, even a well-designed antibody test cannot guarantee that a person is immune to SARS-CoV-2.

Even with these elements of uncertainty, I’m confident that antibody testing will become part of our strategy in the coming weeks. Scientists are studying the serum antibodies of people who have recovered from COVID-19 to try to get the answers we need. Even if a minor bout of COVID-19 does not confer strong, long-lasting immunity, it probably provides at least some protection in the short term.

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

Do you like my science journalism? Read Science in the Neighborhood and learn, where does my tap water come from? How are mosquitoes managed? What happens after I flush? Where does my electricity come from?

Do you like my science journalism? Read Science in the Neighborhood and learn, where does my tap water come from? How are mosquitoes managed? What happens after I flush? Where does my electricity come from?

0 Comments

Share this:

0 Comments