America Dances (part 3): How did we get here?

Source: New York Times

America Dances (part 3): How did we get here?

When I was young I learned a saying: You made your bed, now you have to lie in it.

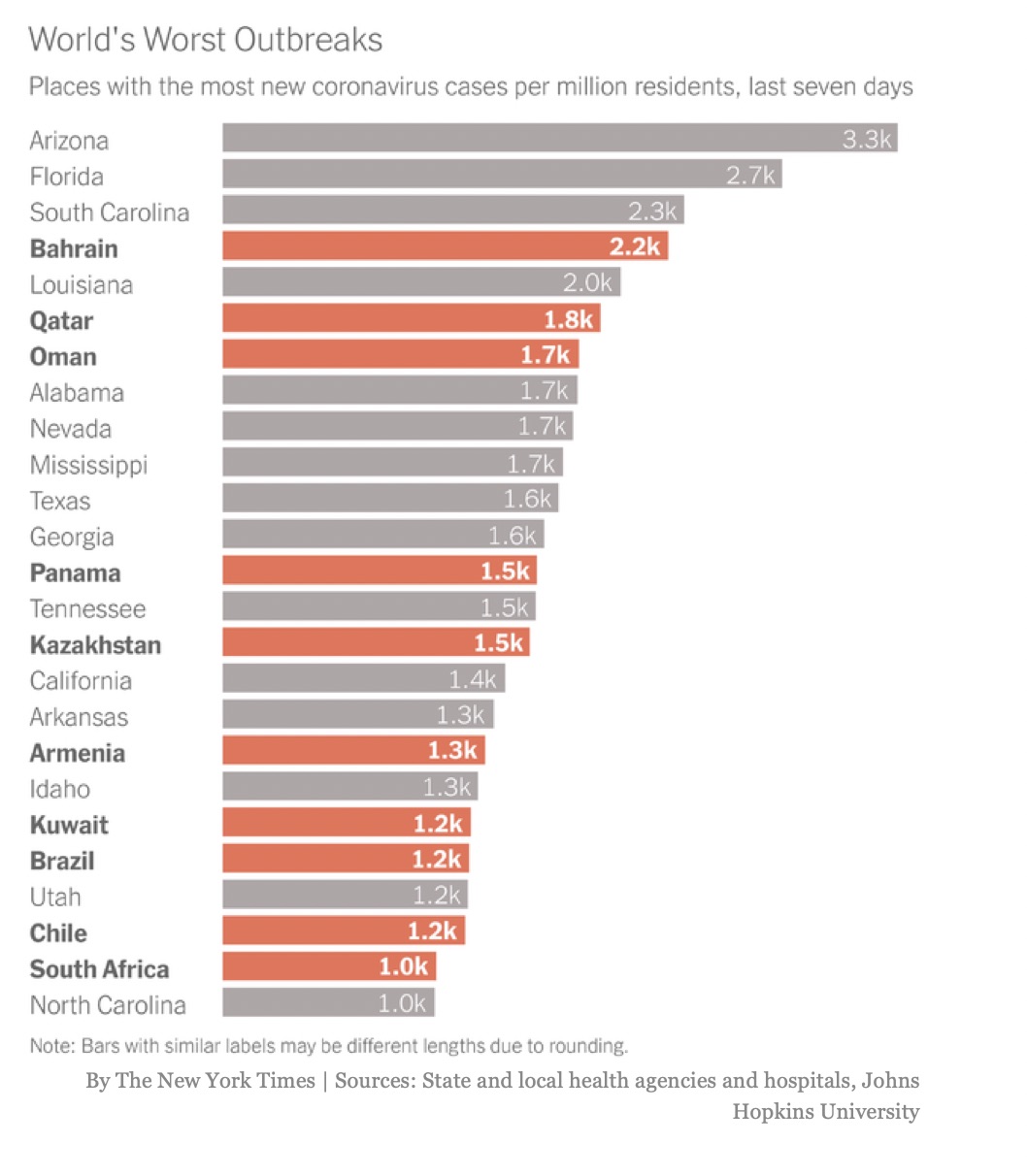

As I demonstrated in my previous post, the United States has made its coronavirus bed, and it’s not as comfortable as the one in Europe. American states treated as countries occupy ten of the fifteen top slots for worst outbreaks of the coronavirus in the last seven days (see figure above). No European countries are in the top 25.

Why did the US choose this path?

It’s not because we didn’t have access to the same epidemiologic advice that the Europeans did. Part of the problem is we didn’t really choose it. We collectively stumbled into it as the summation of countless political, economic, and personal decisions flailing in the absence of decisive, effective national leadership. In that sense, we got what our “national character” wanted.

I could write for days about specific policy decisions, but that wouldn’t really explain why. Here are five underlying factors that drove the decisions that got us here:

- A narrative that the cost of suppressing the pandemic is not worth the benefit

- Mistrust of expertise

- Mistrust of government

- Toxic individualism

- National leadership failure

“It’s just a touch of flu”

The first factor is the “rational” one. It’s the one argued in op-eds, the one that can be evaluated with data. Early in the pandemic, when American COVID deaths were in the single or low-double digits, we were drowning in uncertainty. Epidemiologists told us that we needed to act quickly and decisively but it was admittedly very hard to envision a respiratory virus taking down the country. At the same time, the cost and trauma of shutting down everything was quite clear. Importantly, we were not sure how deadly SARS-CoV-2 would be. How many lives were at risk?

This was a fair question. While some people insist on “safety” at any cost, the reality is safety has a price and in terms of public policy, lives have a dollar value. Left unimpeded, would the new coronavirus kill a hundred Americans? Ten thousand? A million? As I wrote in a post back in March, if the virus had 50% mortality, killing one in every two people it infected, I think we would’ve had easy national consensus for a rigidly enforced lockdown. On the other hand, if a new infectious disease was likely to kill only a thousand Americans until herd immunity, the massive economic and social cost we’ve already paid would not have been worth it. Heck, we could’ve used the stimulus money alone to save thousands of lives in some other kind of safety or health program.

But in early March, we had reasonable disagreement about the epidemiologic models built on assumptions about a brand-new virus. A narrative took root saying, Your missed graduation or wedding or funeral, your lost job or failing business, your loneliness are not worth it. Your sacrifice is a waste.

Now the death count is over 130,000 Americans, with probably a potential for 500,000+ if we give up. Is preventing those deaths worth it? That’s a value decision. I’m not going to argue either way. The point I wish to make is that the narrative established earlier hasn’t really been affected by the unfolding reality of the pandemic. Enough Americans embraced the idea that COVID is “no worse than flu” and they are not revisiting that assessment. For them, it all still is not worth it.

The practical consequence of this narrative is a general reluctance or even rejection of physical distancing and the many non-pharmaceutical interventions, and then impatience when lockdown dragged on. If you believed the cost of lockdown far exceeded the benefit in lives saved, of course you were pissed off.

Don’t change your story

Why didn’t the narrative change as people keep dying? That leads into the other four factors in my list. Unlike the first one, these are not arguments. They are poisons. They’re all inter-related and amplify one another. Along with “demonizing The Other,” which played a smaller role in this pandemic and therefore didn’t make my list, these evils summarize much of what’s wrong with America in 2020, pandemic or no pandemic. Their collective influence on how our country has responded to the coronavirus can hardly be overemphasized.

Mistrust

The pandemic has exposed the great social cost of mistrust in 21st century America. Rather than trust highly educated specialists to know things, many Americans think their own ideas on the pandemic are equally valid, or they even actively reject expertise as biased and against their interests. This isn’t about education; few people have sufficient technical knowledge to evaluate expert assessments of the pandemic. It’s about humility (I don’t really know much) and trust (I will listen to someone who is more likely to be right than I am, and I will continue to listen even if they are wrong some of the time). In the age of social media, humility has been murdered by certainty.

Some government actions that could have impacted the pandemic have been impossible because of mistrust. For example, quarantining an infected family member within a household can be futile. In some countries, the government provided hotel-type accommodations to isolate people who were virus-positive but not terribly sick. This stops transmission within the home, which is one of the most significant drivers of the pandemic. In some places, such isolation was forced / mandatory; most Americans would reject that. But trust was too low to make isolation centers work here even on a voluntary basis. Another example: We don’t use mobile phone-based tracking to identify and isolate contacts of people who newly test positive for the virus. Privacy concerns are legitimate, but rampant mistrust of both government and the tech industry meant the US would reject most any form of this technology.

Selfish Freedom

A healthy respect for the dignity and freedom of the individual is one of America’s most admirable traits. But freedom cannot be untethered from responsibility. At times in our exercise of our personal freedom we must choose the good of others over our own good. Toxic individualism fetishizes freedom itself, without regard to the social context. We all have a natural tendency toward selfishness. In a well-functioning society, leaders of all kinds provide a narrative and an example that encourage “the better angels of our nature.” We learn, and we tell each other, that sometimes sacrifice is the highest moral expression of personal freedom. I might not be afraid for my own health, but my actions affect my elderly or diabetic neighbor.

Unfortunately the pandemic has amplified the voices of those who put freedom ahead of responsibility. At its most obvious extreme are those who respond violently to mandatory face masks. It’s one thing to doubt the experts who say that masks protect other people from your asymptomatic infection; reasonable people can disagree about data. It’s something far worse to scream that the well-being of others has no bearing on your right to do whatever you want.

Leadership

Finally, I have to call out the president. In my coronavirus blogs I work hard not to say things that trigger people’s tribal anger, because then they stop listening. But on this issue, I have to say that Trump has been a disaster for our country. I certainly don’t blame him for everything that went wrong in our pandemic response. This was a monstrous challenge for any administration. The federal government is an uncontrollable behemoth, and when agencies fail to carry out their duties it’s not always the fault of the Oval Office. However the president’s personal responsibility to the nation in crisis was to provide leadership. By this I mean first of all a coherent vision, grounded in science, formed by clearly articulated values, that spelled out the necessary tradeoffs and recognized the necessary pain, and that gave consideration to the vulnerable. Such a plan could’ve favored red-state values. But instead he offered pipe dreams and denial. He failed to inspire or to model good behavior, instead amplifying mistrust of experts by contradicting his own coronavirus team and promoting his gut feelings more than data. He fanned mistrust of government by promoting conspiracies. Rather than encouraging cooperation, he left the states to directly compete for scarce resources. He delivered no compassion and didn’t use the language of shared sacrifice to foster patience or generosity.

These failures impacted the federal response and they influenced us and our billions of individual choices about NPIs. As much or more than government policy, our collective decisions to host a party, visit a bar, skip the mask, give a hug, etc. have landed us where we are now.

NEXT: America Dances Part 4: Is there an American advantage?

Amy Rogers, MD, PhD, is a Harvard-educated scientist, novelist, journalist, and educator. Learn more about Amy’s science thriller novels, or download a free ebook on the scientific backstory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging infections, at AmyRogers.com.

Sign up for my email list

Share this:

0 Comments